We Struggled Without Afterschool Care in the 80s. Two Million Parents Today May Struggle Again.

by Rhonda Bryant

The issue of access to afterschool programs is one that is deeply personal for me. When I was 9 years old, my family lived in northeast Washington, DC. We’d recently moved there, and we didn’t have family or friends living close by. I was in the 4th grade, and my brother was in 2nd. We attended LaSalle Elementary, our neighborhood school that was just a block from our home. My mother would see us off and we would walk there every morning. But after school, she was still at work. There was no free or affordable afterschool program in or near our school, and that was an extra cost that my mother simply could not afford.

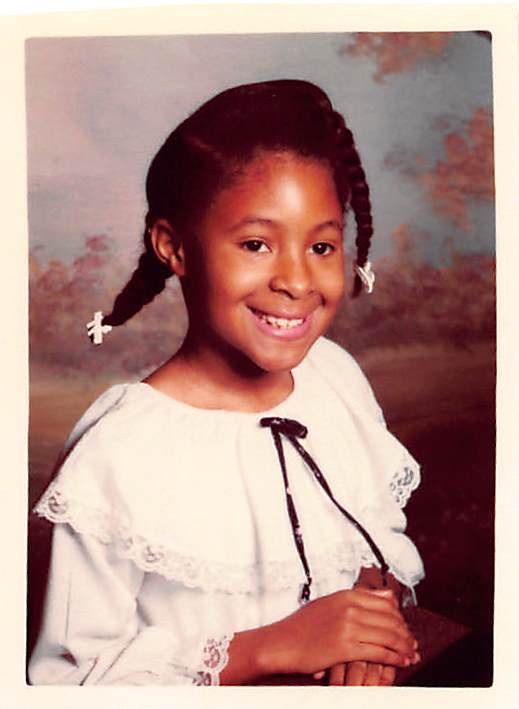

So my brother and I were “latchkey kids.” We would walk home together and then call Mom at work to let her know we were safe. Then I’d make us a snack and we would read, do homework, and watch tv until Mom made it home. But my mother hated this and, secretly, I did too. I mean, really, look at that picture — does that little girl look like she can care for herself and a younger sibling for 3 hours a day? I’d never complain though because I knew my mother was doing the best she could.

A few weeks into the school year, the newly-built Lamond-Riggs Library opened in our neighborhood. My mother, being the resourceful and creative woman that she is, paid the librarians a visit. She was determined to figure out something so her two kids weren’t unsupervised each day for 3 hours. She worked out a deal with them so that, as long as we were quiet, we were allowed to stay there until she got off of work. A few other desperate parents had the same idea, and so a group of us walked together to the Lamond-Riggs Library every single day after school. And there we’d be — our little crew — doing homework, reading books, and playing games until one by one, our parents arrived to pick us up.

My mother did this for eight years. As we moved through middle and high school, she would just get to know the librarians at whichever library was closest, and that’s where we would go. She could not afford anything else. The fact that a responsible mother with a masters degree and full-time professional job could not afford the cost of afterschool child care on her salary is an economic issue in itself, but that’s another post entirely. She was not alone — many of her friends were in a similar predicament, feeling stuck and scared with nowhere safe for their children to go when school dismissed at 3pm. Those librarians gave my mother a precious gift — a free, safe place for her children.

The nation’s 21st Century Community Learning Center (21st CCLC) program wasn’t created until I was a college student. The program was started, in part, because America recognized that the hours of 3–6 pm, when children were unsupervised, were the most dangerous hours of their young lives. Organizations like Fight Crime, Invest in Kids threw their full support behind programs like 21st CCLC because they recognized the need to invest in solutions that kept kids safe and productive. Since then, millions of children whose parents otherwise could not afford it have had safe places to go after school. Two-thirds (67%) of participants in 21st CCLC qualify for free and reduced lunch, and more than 70% of participants are children of color.

Research compiled by Afterschool Alliance shows that students who participate in afterschool programs have better academic performance, better attendance, and are less likely to drop out of school. Schools have decreased behavioral incidents, and kids are less likely to engage in risky behaviors. More than 8 in 10 parents agree that having children in afterschool programs helps parents keep their jobs and gives parents peace of mind about their children while they are at work. The demand for afterschool services, however, far exceeds the amount of services available. About 19 million parents report they would use afterschool services for their children if they were available. Hispanic and African-American children are currently at least two times more likely to participate in an afterschool program than Caucasian children, and the unmet demand for afterschool programs is also higher for Hispanic and African-American children.

With outcomes and demonstrated needs like these, it is unfathomable that the Trump Administration is proposing to eliminate this program in their 2020 budget proposal.

Eliminating 21st CCLC will hurt working parents of color, who are less likely to have flexible work schedules or paid leave. It will increase their level of worry about their children, and also make it more likely that they will lose their jobs in the event their child has an emergency after school. It will steal opportunities from students of color who need these programs to support their academic success. It will impair the work of teachers, who will have to do so much more to help their students learn. It will also increase policing in communities of color, because a lack of afterschool programs practically guarantees an uptick in risky behaviors, as idle young people make mistakes and get into trouble. Knowingly creating these adverse conditions, particularly for those who can least afford to have opportunities and options taken away from them, is simply inhumane.

My first job after graduate school was working in a community center that offered afterschool programs to neighborhood children. My enrollment was 100% students of color. The federal funding we received allowed us to serve children for a nominal cost to parents. I literally saw hundreds of students each week. For those precious afterschool hours, they were MY babies. I collaborated with their parents and their teachers to pour into them everything I knew to give. I taught them how to read, practiced math drills, helped them create elaborate science projects, taught them about other countries, ran an SAT prep program, and helped them complete college applications and essays — all while their parents were hard at work trying to earn the money necessary to support their families. When my students excelled, my heart soared. They are now adults, and many of them have shared with me how the seeds sown in our afterschool program made a difference in their lives.

We know that afterschool programs work. They work for all students and, quite frankly, fill a particular need for students of color and their families. We must ensure that 21st Century Community Learning Centers don’t go away. Afterschool Alliance, a national leading organization working to ensure that all youth have access to affordable, quality afterschool programs, has developed an interactive map to show how this proposed cut would adversely impact students in each state. Check out the tools developed by Afterschool Alliance to see how you can make your voice heard and save funding for afterschool.