A Mother’s Love Liberates

This is how I show my love. To liberate his mind from the chains of dehumanization that threaten to drag him down when he wants to soar. To transcend the negativity, and instill a hope that stirs up in him the strength to thrive.

American Education Research Association – Annual Conference

Date: Time: Workshop Title: Workshop Description: Presenter:

Association of Black Foundation Executives – 2019 Conference

April xx, 2019 Time Workshop Title and Description Presenter:

Funding Quality Afterschool Care

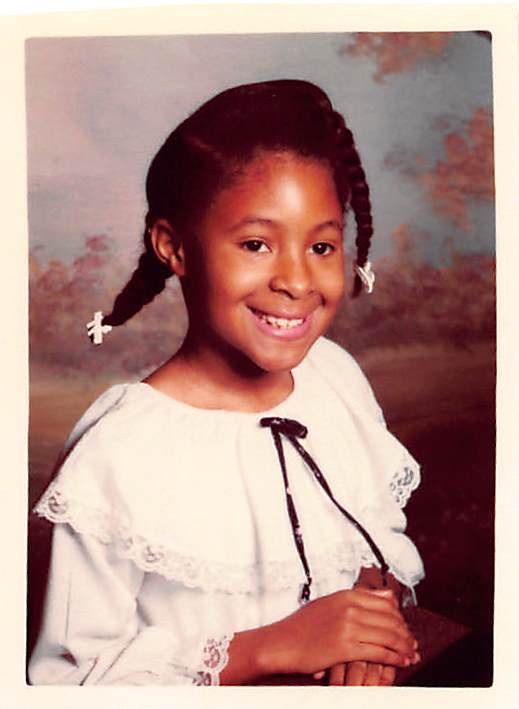

We Struggled Without Afterschool Care in the 80s. Two Million Parents Today May Struggle Again. by Rhonda Bryant The issue of access to afterschool programs is one that is deeply personal for me. When I was 9 years old, my family lived in northeast Washington, DC. We’d recently moved there, and we didn’t have family […]