Celebrating Liberation: A Personal Reflection on Juneteenth

Then, it hit me like a ton of bricks: my grandfather was actually a sharecropper, and this was over 100 years after those 250,000 enslaved people were deemed free!

Celebrating Mother’s Day: Lessons on Tenacity, Family, Faith, and Community

If you ask my mom to describe my leadership style, she would say that I’m a protector; it’s ingrained in my personality. Looking back at my nine-year career as a business owner, I would agree with her. My major accomplishments have always involved championing others and wanting to be a protector of people. An old […]

An Open Letter of Support to The Justins and Boys and Young Men of Color

In this Open Letter, Rooted Change—the newest initiative created by The Moriah Group—is expressing its solidarity with Tennessee State Representatives Justin J. Pearson and Justin Jones who were expelled from the House of Representatives over their protest against gun violence. They have since been reinstated, but we affirm their unequivocal right to fight for racial […]

Ericka Plater Seeks Equity for Young People and Healing for Communities in New Leadership Role

As Senior Director of Executives’ Alliance (EA), now housed within The Moriah Group, Ericka facilitates a network of philanthropic and field leaders to collectively dismantle the systems and narratives that traumatize young people of color. Her expertise spans education, philanthropy, health, community development, and direct service in nonprofit leadership. She is also deeply passionate about […]

Evolution: Three Organizations Reclaiming Our Humanity #ROH

We are excited to introduce a new look for Forward Promise and The Moriah Group!

Leading with Love, A Women’s History Month Reflection

Women’s History Month is always an introspective time for me. I think about all the ways that women have been, and continue to be, visionary shapers of their communities.

As Schools Reopen, How Should They Meet the Needs of Students of Color?

With COVID-19 an ever-present threat, many parents are burdened with questions as some school reopen for face-to-face instruction.

“I AM HUMAN,” a film project of Forward Promise.

Ask a young child what they want to be when they grow up and they will likely give you a list. Their dreams are boundless and they derive genuine excitement from planning their future.

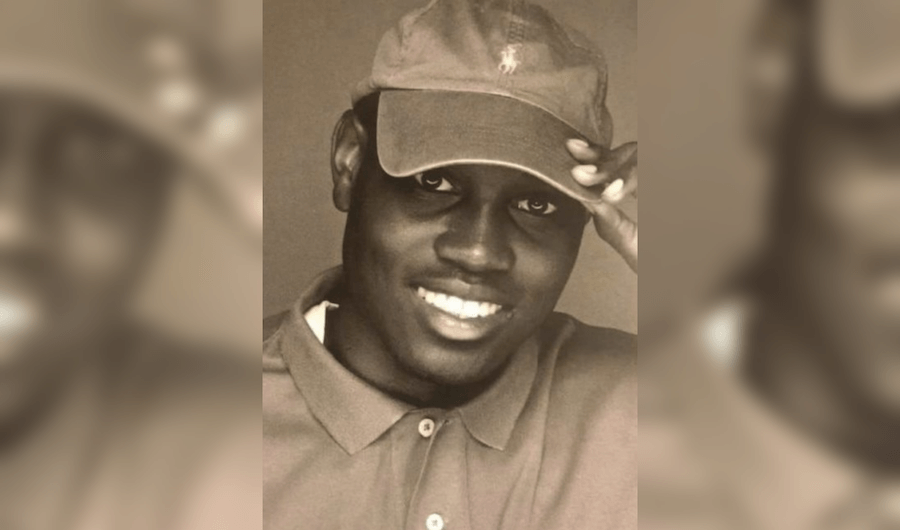

Justice for Ahmaud Arbery: Dehumanization Is Not Normal

Jogging on a sunny spring day is normal. Chasing, shooting, and murdering a Black man while he is jogging is NOT normal.

A Mother’s Love Liberates

This is how I show my love. To liberate his mind from the chains of dehumanization that threaten to drag him down when he wants to soar. To transcend the negativity, and instill a hope that stirs up in him the strength to thrive.